On Thursday and Friday last week, I had the honor of being one of the invited guests of the experimental and truly wonderful conference “Cartooning the Medieval,” hosted by the Newberry Library and organized by Christopher Fletcher and Kristen Haas Curtis. The conference was born out of Kristen’s desire (as a cartoonist with a recent PhD on Chaucer) to put cartoonists and medievalists in the same room and see what happens. I am still processing the event, which is an enormous compliment! Half the attendees were cartoonists and the other half were academic medievalists; the organizers did a lot of work to cultivate cross-disciplinary thinking and collaboration, and the feeling in the room shifted from slightly nervous fish-out-of-water bemusement to extreme enthusiasm. We also got to handle and spend contemplative time with medieval books from the Newberry’s collection, which was unimaginably special. (If you’re 14 or older and walk into the Newberry when they’re open, you can ask to sit with these 800 year old books and leaf through them, no institutional affiliation required! Amazing.)

Lucy Bellwood, Chris Schweizer, and myself were the “embedded artists,” and we were invited to present what we discovered in our time at the conference with, generously, no expectations on what that talk or presentation would look like. However the spirit moved us was fine! Thursday we got to have a private introduction to the books that everyone else would see the next day, then after lunch was the opening day keynote speeches and talks, followed dinner out with the group. I woke up at 5 the next morning panicking about what in the world I could talk about for 20 minutes, so I got to the Newberry early to sit in the park and draw and think, hoping that I could find something coherent to say. The day was packed with interesting events and activities, so I stole away to the park again after quickly eating lunch to write down all my thoughts. Among the many things I’ll take away from this experience is a new confidence in my ability to find something to say on the fly! Here is my artist talk, untangled in the morning and written down between 1 and 1:30pm last Friday, and delivered at 4pm at the Newberry in front of a room of cartoonists and academics. No pressure.

Artist Talk: Cartooning the Medieval

June 6, 2025

I have been thinking since I first arrived yesterday: why am I here?

The easy answer is that I am a cartoonist at a conference for cartoonists, and that Kristen generously thought of me as a person who might get something out of an event like this, and who might have something to share. But I’m not being self-deprecating when I say I don't think, in the wide world of cartoonists, that I am an obvious choice.

I don’t make historical comics, or nonfiction comics, or comics inspired by the aesthetics of the medieval era. I don’t make work set in a romantic or gritty fantasy reimagining of the Middle Ages. If comics is a medium, the genre in which I work is comic poetics. I’m interested in visual metaphors, in the potential for juxtaposition of image and text to create complex layers of meaning. I am working on every page to use the alchemy of my craft to weave image and text together in a way that captures something ineffable, and to try to trick your brain and body into feeling the same thing I am. Right now I am working on a big graphic memoir where I think deeply and critically about what it means to let yourself be transformed by an experience. It is about motherhood, about grief and anger and love…and about wild animal attacks where people are eaten alive.

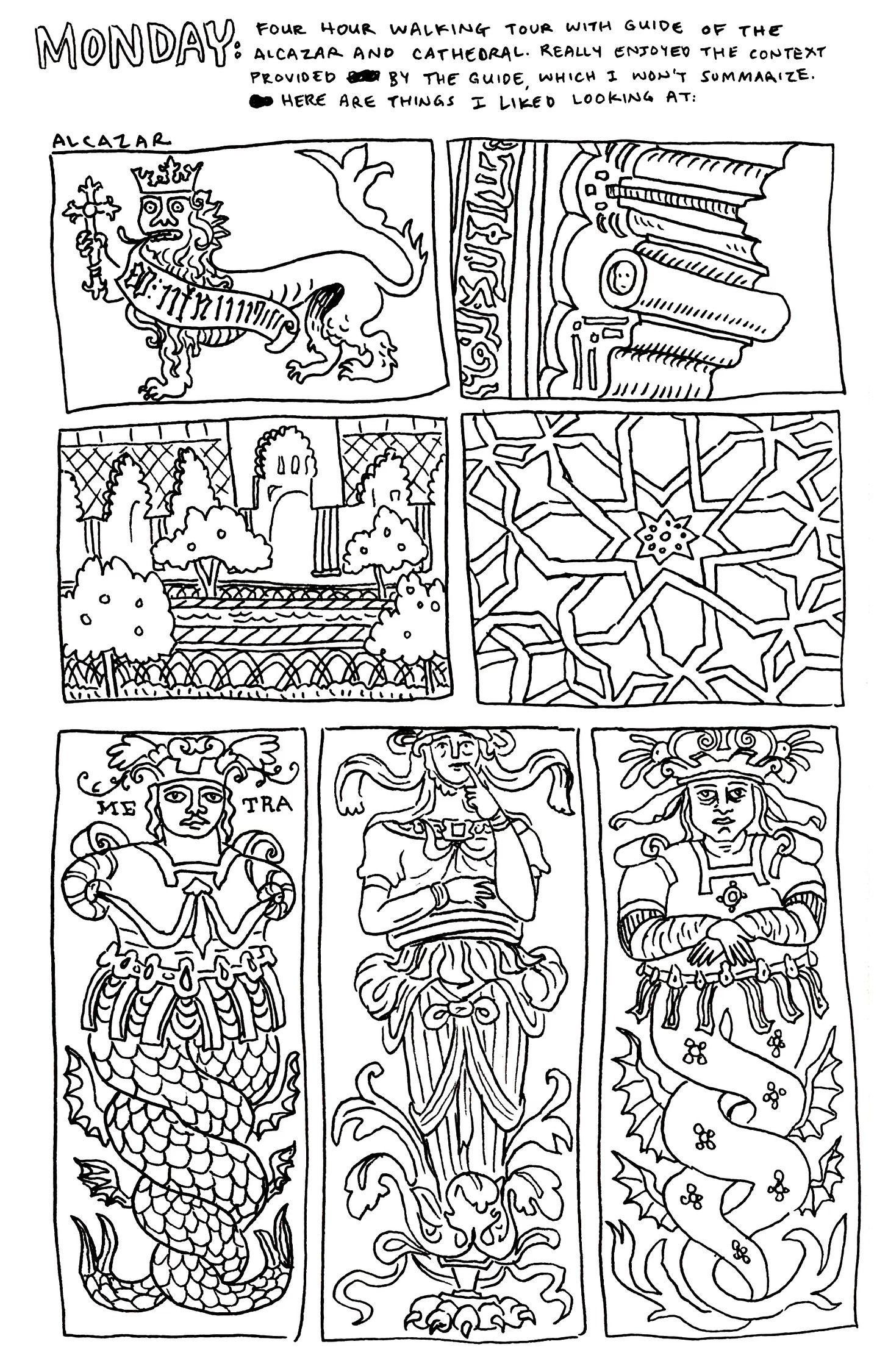

I also make diary comics, drawing scenes and conversations from my day in quick-to-ink panels with no pencil sketch, as part of a lifelong effort to loosen up. It also serves as a place to hold my memory, acts as a gratitude practice, and has become a place for me to hold myself accountable, as much a commitment to my craft as to my moral ideals. Can I honestly draw myself as the person I wish I were? Certainly not every day. To my understanding coming into this conference, neither of these branches of my creative practice are terribly medieval.

(Show Cuarenta, talk about anxiety coming here: “at least I can show that I drew some medieval guys!”)

I have joked before that making comics feels monastic, like I’m illuminating manuscripts in the corner of my living room, so I made a drawing and a print to finally have a place where that very specific joke might land. I made this print to trick you all into thinking I had a reason to be here.

All of that is to say: I came into this experience curious and open hearted, and feeling a little out of place. I have been delighted to find myself so completely at home. Here are some of the connections I have found:

A connection to the lineage of artists and craftspeople and thinkers who work with ink and pigment on paper

A connection to very specific medieval process: pricking and scoring is very much like what I do with my blue pencil and Ames guide, to help create consistency in my lettering

A connection to the individuals who made those specific books: I loved seeing the ledger book where the keeper of the book crossed out the mundane and started documenting the deaths of community and family members during the plague. I did something similar: I started my diary comics practice during Covid

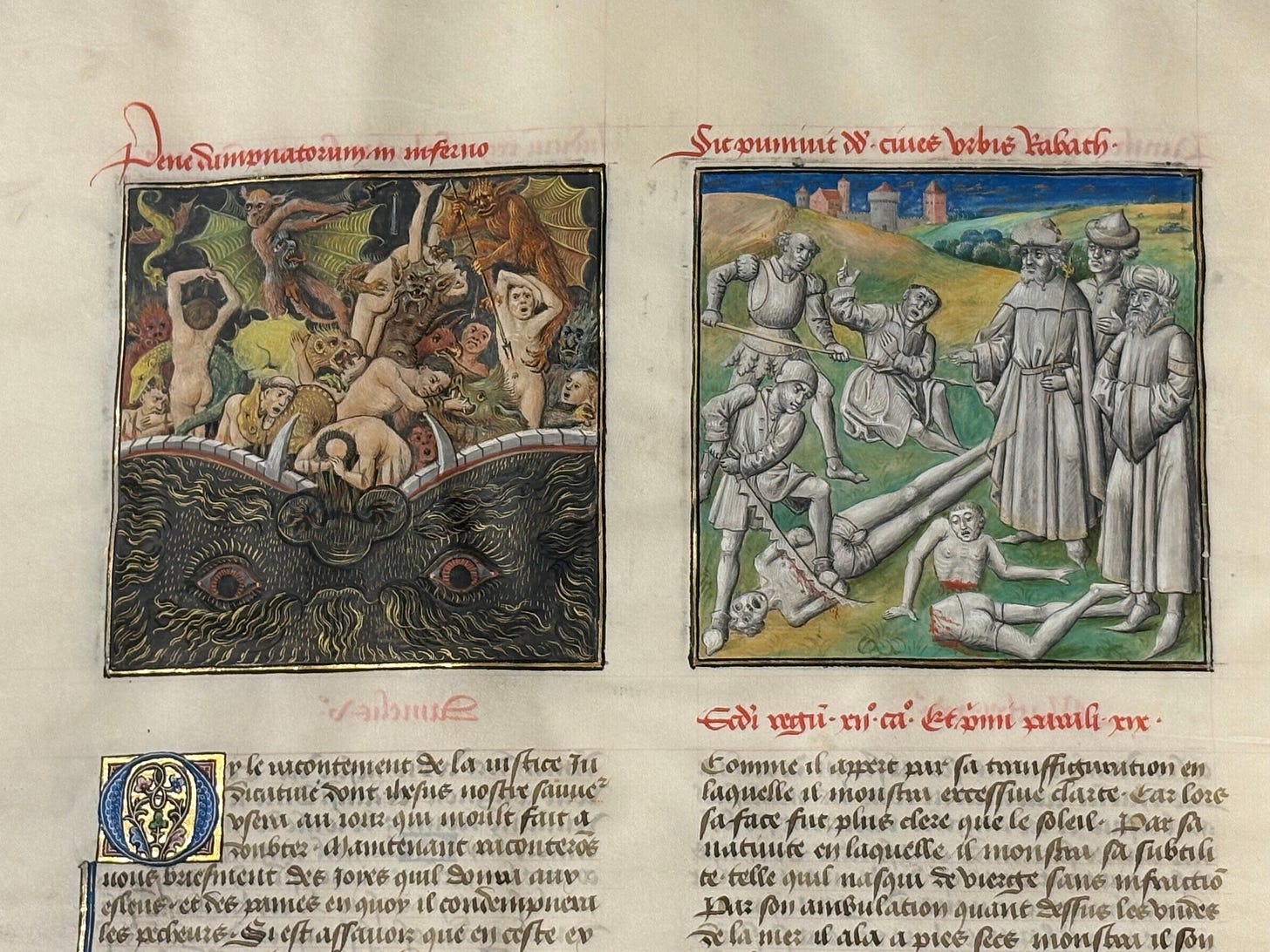

I also felt the deep sensory pleasure and awe at being in the presence of such old objects. I felt connected with the aesthetic of abundance on the pages we looked at from the collection, the density and precision of the script and of course the beauty of the illumination. I did not bring any work that represents an aesthetic that I became best known for, but as an artist I am interested in beauty and sumptuous maximalism as a Trojan horse for something weirder or harder, where the beauty of the page draws you into a tiger’s den. I love this about medieval manuscripts too: our breath is taken away by the gilded details and the rich blue flora, but the images are of beheadings or demon-beasts and they’re surrounded by weird little guys in the margins. That feels so human to me, dealing with the horrors and ecstasies of being alive by gilding it and being very silly with it. I also sneak in surprises in pages of dense abundance, to reward and to undermine a close reading.

I was also moved by the realization that these books survived, in no small part, because of their beauty. I do, too. I survive because of the beauty of the pages I illuminate. I survive because of the beauty of the world.

I also want to talk a little bit about cartooning and the work we got to see from the collection. Please follow along with me:

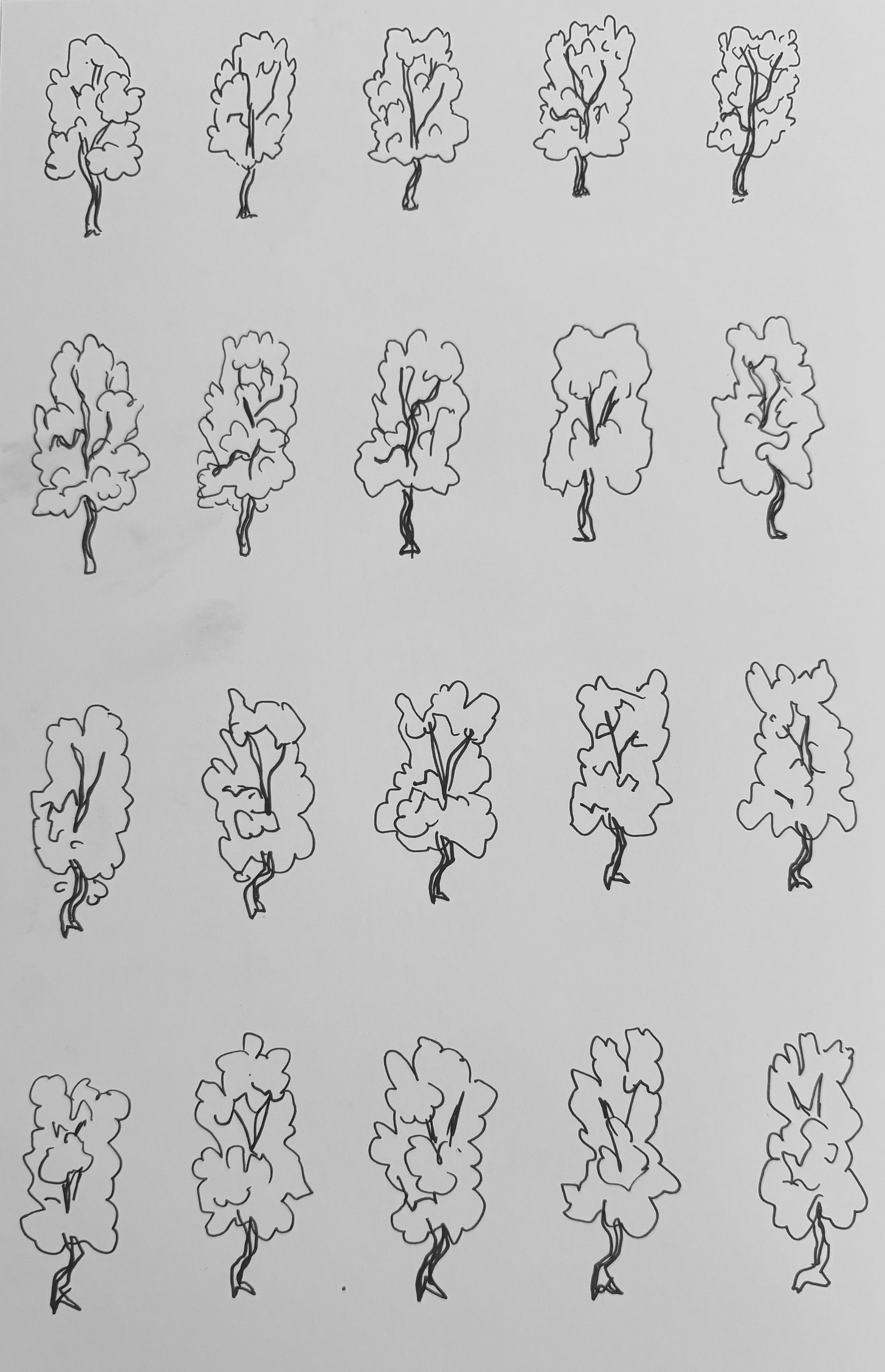

There is a difference between drawing an idea and drawing something that exists. If I need to draw a tree quickly, I’ll probably doodle the same thing I have since childhood: two straight vertical parallel lines and a fluffy top. This is a representation of an abstract idea of Tree. An icon.

If I sit in the park across the street and draw a catalpa tree on the east side of the fountain, that is a specific tree, unique in the history of the world. 20th century Trappist monk and theologian Thomas Merton said, “the flowering dogwood tree is a saint.” It is unique in creation, fulfilling its existence by being exactly itself. I find this kind of drawing the closest thing I have as a secular person to prayer. It is quiet meditation, and I am giving my whole attention to honor the shapes and forms and surprising imperfections of this one tree on this one day; the act of observing and drawing is a devotional. (When I was drawing a panel from a book yesterday, I chose it because of an amazing beast swallowing some men with crowns, but I was surprised when I spent the time looking and drawing that there was also an unassuming pigeon in the opposite corner. What a surprise!)

What I find interesting about comics is that something similar (and for me, approaching sacred) can happen when you draw an icon *enough times*. An icon can move out of the realm of the platonic abstract and becomes something more mundane, more of the world. If I draw a 100 page comic and I set it in the park across the street, I will draw a simplified version of that one specific catalpa tree, because comics is an efficiency machine—drawing something enough times, it gets streamlined, simplified.

But this is where the trick comes: If I draw the icon of the tree 500 times, the icon itself becomes real to me. I close my eyes and see it; I can draw it in my sleep. It becomes a sense memory in my hand and a part of my imagination much more vividly than the real life tree.

I have been thinking about this a lot since yesterday morning, when we “embedded artists” were given a private audience with the illuminated manuscripts. When the medieval cartoonist sat at their table with their parchment and drew, for instance, the devil as a blue beast with chicken feet, I wondered: are they drawing the specific devil as they understood it, or an icon? My first instinct to answer this is to say it is an icon, it is a representation of the idea of the Devil, but did the act of drawing it make it more real for the artist? Did it make the idea of it more real for the people reading this manuscript? I am sure that these are rudimentary questions of medieval scholarship, but sitting with these books I could easily imagine myself sitting at a blank page and having to figure out how in the world I was going to draw a devil, and I’m not sure if I was given 500 pages of parchment if I would have come up with that specific blue guy with chicken feet, even if there is a long history of describing the devil this way. The hand of the individual artist is on that page, interpreting the divine with their own hands. I find that thrilling, and deeply relatable.

I’m going to paraphrase something Chris said to the cartoonists today, sitting amongst medieval manuscripts: I have learned that an inherent part of being a medievalist is an act of looking and decoding, and being comfortable sitting in the mystery. Being willing to sit through an initial sense of confusion and figuring out what a book is about. I do the same thing when I look at the catalpa tree. I do the same thing when I fight against a blank page and try to help it unveil its mysteries by layering blue pencil and ink and pigment.

I want to leave this with a thanks to Kristen and Chris, to the Newberry and all the amazing scholars and staff who hosted us today, and to everyone in attendance. To everyone in the room, I also want to invoke a call to action, medievalists and cartoonists alike. I invite all of you to draw more. Draw your ideas and questions, draw what you had for breakfast, draw the weirdest panels in the medieval manuscripts, draw the trees outside. The act of drawing is just as much an act of thinking as writing prose scholarship. It is anti-pretentious and can be deeply intellectual, and is part of a long history of people sitting at desks illuminating manuscripts, trying to decode the heavens and the meaning of it all. We are a part of that too.

Thank you.

This was such a gorgeous talk. Thanks for sharing! I also love that the catalpa tree looks like animated cells of a very coy catalpa executing a fan dance. That is one sassy trunk on her.

I loved this, thank you for sharing!